Invisible "Magical Processing": How Low-Temperature Plasma Modifies Material Surfaces?

Have you ever wondered why the glass surface of your phone can respond to touch accurately and resist fingerprints? And when doctors use medical devices implanted in the human body, what enables synthetic materials to "coexist harmoniously" with human tissues? Behind these seemingly ordinary functions lies an invisible "black technology" — low-temperature plasma surface modification technology. This technology, which uses the "fourth state of matter" to modify material surfaces, is quietly transforming our daily lives and industrial production.

To understand this technology, we first need to figure out what "low-temperature plasma" is. Matter as we commonly know it exists in three states: solid, liquid, and gas, while plasma is the fourth state of matter. Simply put, when sufficient energy (such as electric field excitation) is applied to a gas, some of its atoms or molecules lose electrons, forming a mixed system composed of positive and negative ions, free electrons, and neutral particles. This system is electrically neutral overall, and that is plasma. Unlike high-temperature plasma (such as the plasma in lightning and nuclear fusion), low-temperature plasma is close to room temperature and will not damage the treated materials — this is the key advantage that allows it to be widely used in material processing.

Some people may wonder: why do we need to specially modify material surfaces? In fact, many materials have excellent "core properties" but unsatisfactory "surface characteristics". Take common plastics for example — they are lightweight and low-cost, but their surfaces are smooth and highly inert, making them difficult to bond with other materials or be wetted by water. Another example is biomedical materials: if their surfaces lack biocompatibility, they may trigger rejection reactions when implanted into the human body. The core function of low-temperature plasma technology is to precisely "reshape" the physical structure and chemical properties of material surfaces without altering their internal properties, enabling the materials to "maximize strengths and minimize weaknesses".

The "modification logic" of this technology is clear: high-energy particles (such as electrons and ions) in low-temperature plasma collide with the material surface, breaking the original molecular bonds on the surface. Then, new functional groups are introduced or the surface roughness is adjusted as needed, thereby achieving specific functions. Specifically, it can mainly accomplish three types of "modification tasks".

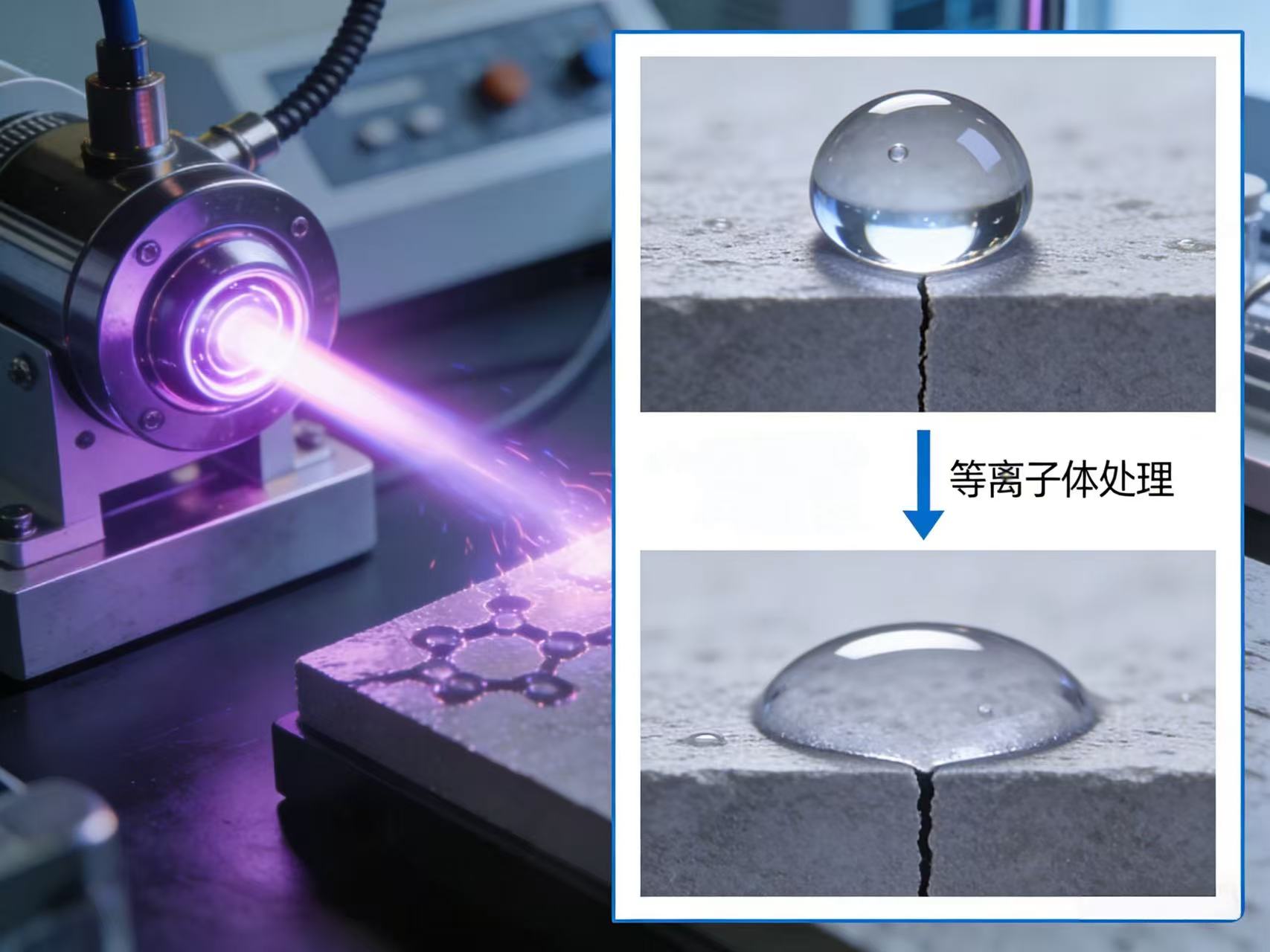

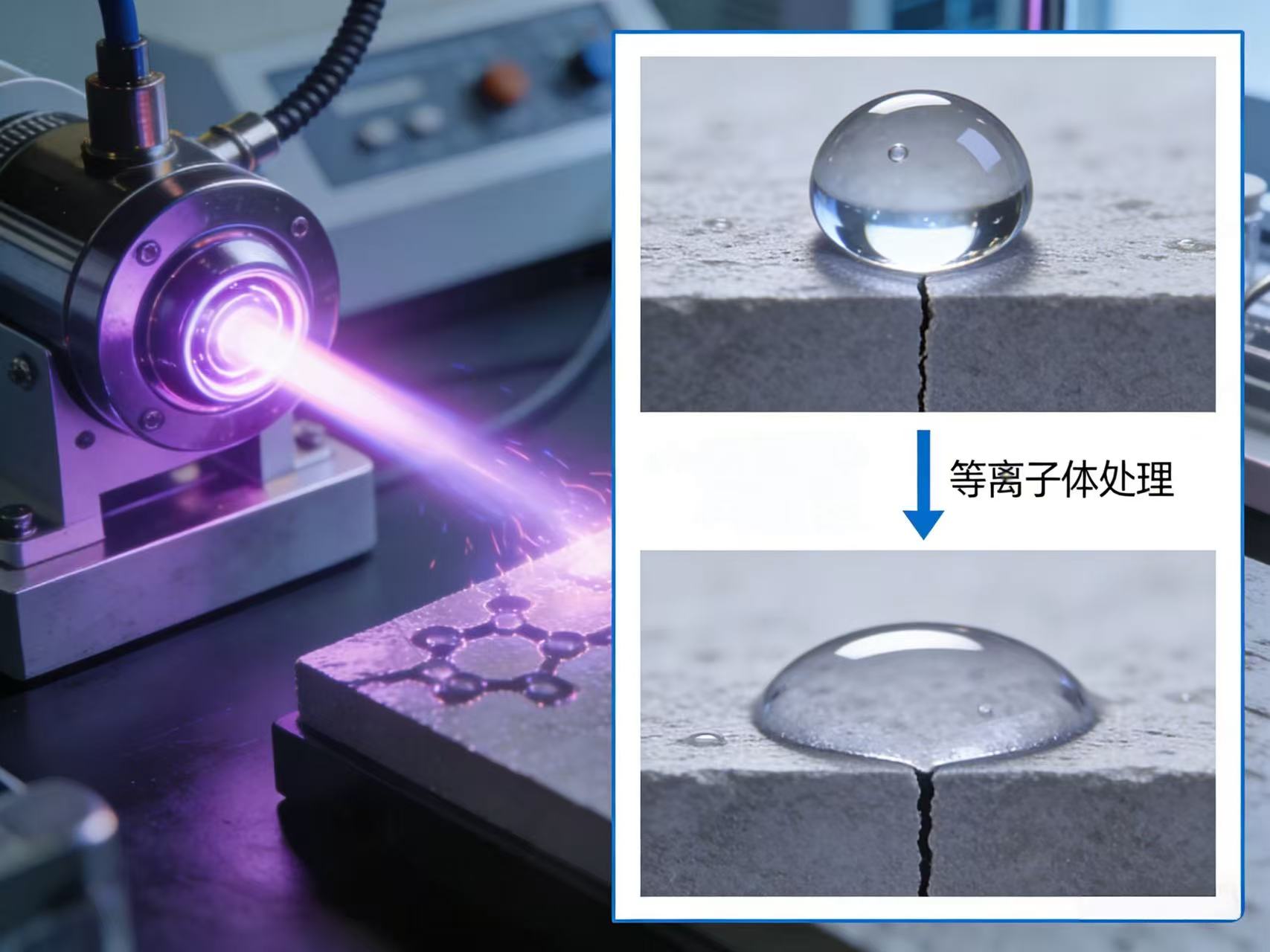

The first is "enhancing hydrophilicity", turning hydrophobic materials into hydrophilic ones. For the plastic films commonly seen in daily life, water droplets roll off quickly when falling on them — this is the hydrophobic property. However, in industries such as packaging and printing, materials are required to absorb inks or adhesives evenly, and hydrophobic surfaces can cause problems. After treatment with low-temperature plasma generated from gases such as argon and oxygen, polar groups such as hydroxyl (—OH) and carboxyl (—COOH) are introduced onto the plastic surface. These groups act like "small hooks", firmly capturing water molecules and allowing water droplets to spread evenly on the surface. Materials treated in this way can not only meet the requirements of printing and coating but also make fabrics more moisture-absorbent and breathable in the textile industry.

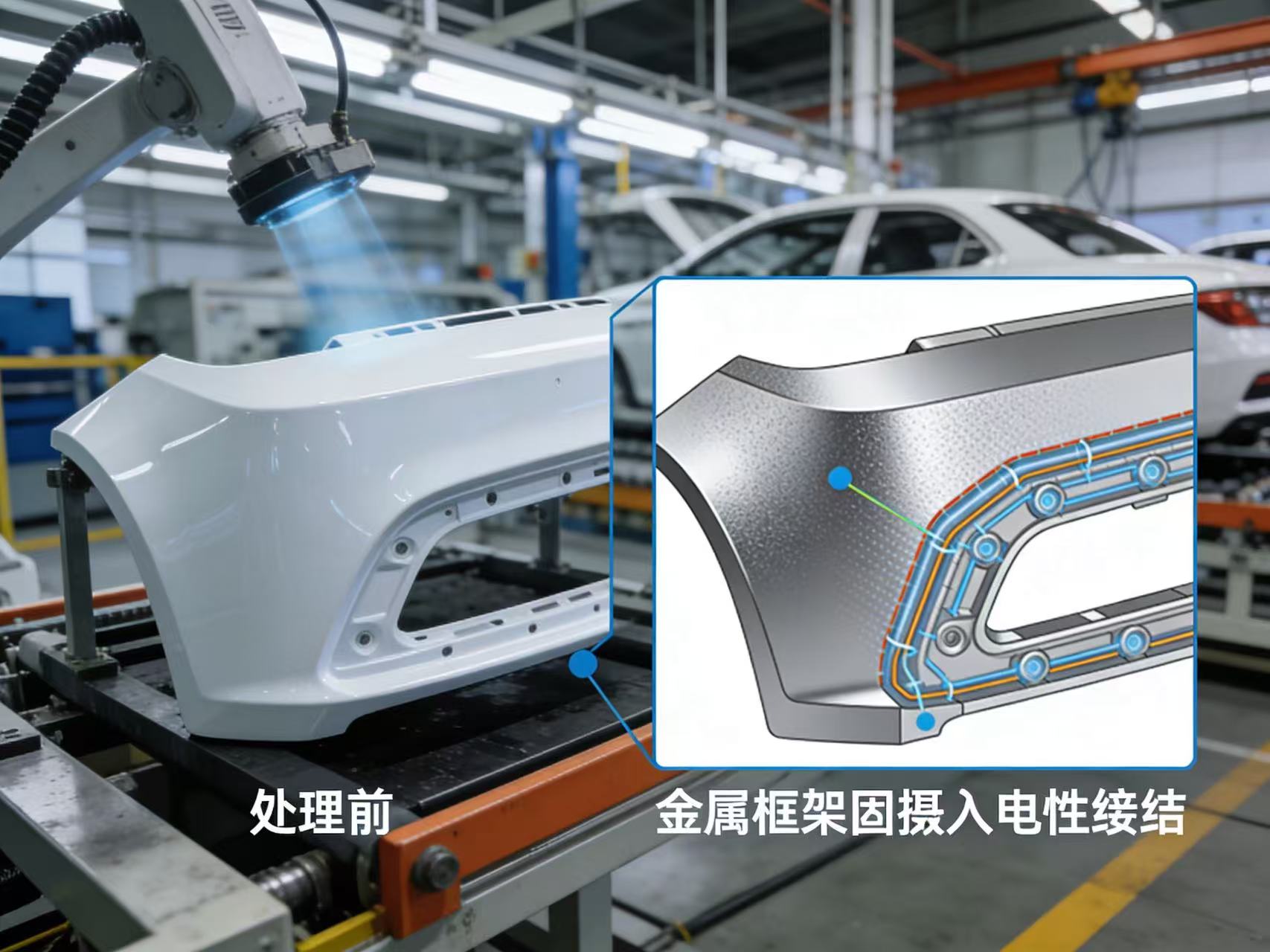

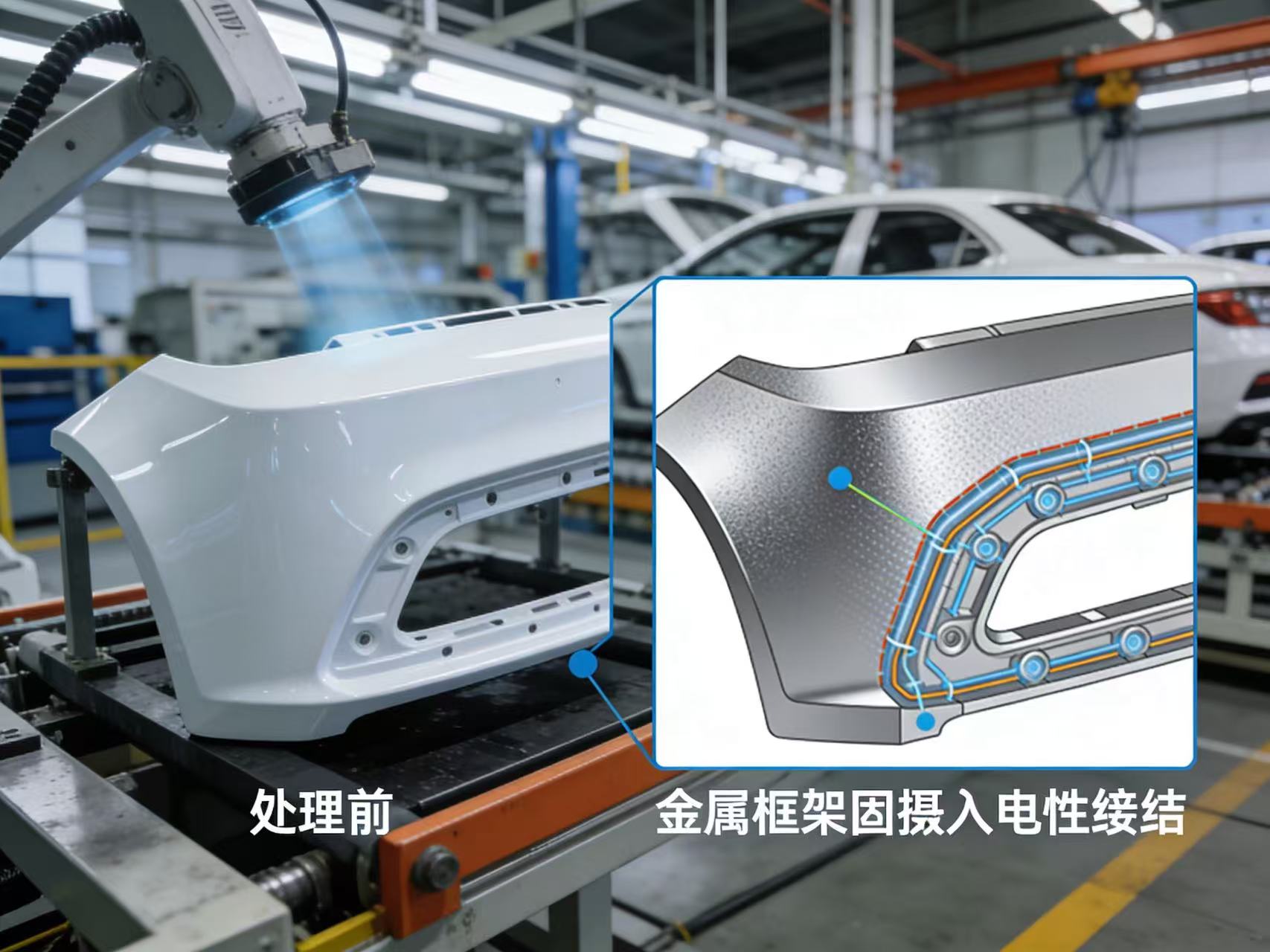

The second is "improving adhesion", solving the problem of bonding different materials. In automobile manufacturing, the bonding of plastic components to metal frames and the fixing of glass to rubber sealing strips all require extremely high bonding strength. In the electronics industry, chips also need to be firmly bonded to substrates during packaging. However, many polymer materials have extremely low surface energy, making it impossible for ordinary adhesives to adhere to them. Low-temperature plasma treatment can break the inert molecular bonds on the material surface, form active sites, and increase surface energy at the same time, enabling stronger intermolecular forces between the adhesive and the material surface. After such treatment, materials that were originally difficult to bond can achieve "seamless connection", with bonding strength increased several times. Moreover, it eliminates the need for toxic chemical primers, making the process more environmentally friendly and safe.

The third is "optimizing biocompatibility", which "escorts" biomedical materials. When biomedical materials (such as artificial joints, cardiac stents, and medical catheters) are implanted into the human body, they come into direct contact with blood and tissues, and their surface properties directly determine the body’s rejection response. Through treatment with low-temperature plasma generated from gases such as ammonia and oxygen, bio-friendly functional groups like amino groups (—NH₂) can be introduced onto the surface of medical polymer materials. These groups can promote cell adhesion and proliferation, and reduce the human body’s rejection of the materials. For instance, treated artificial joints can fuse better with bone tissues; the surface of treated medical catheters can reduce bacterial adhesion and lower the risk of infection. This application allows more synthetic materials to serve the medical field safely, bringing benefits to patients.

In addition to these three core applications, low-temperature plasma technology can also achieve "precision cleaning" and "micro-nano etching" of material surfaces. In the semiconductor industry, it can remove tiny contaminants and oxide layers from the surface of silicon wafers, providing a clean substrate for chip manufacturing. In the production of micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS), it can perform high-precision micro-nano etching on materials to fabricate tiny components such as sensors and actuators. Compared with traditional chemical treatment methods, low-temperature plasma technology does not require large amounts of chemical reagents, does not produce toxic wastewater or waste gas, and features a fast and controllable processing procedure, which is in line with the development trend of green manufacturing.

Today, low-temperature plasma surface modification technology has permeated multiple fields such as electronic information, automobile manufacturing, biomedicine, and textile printing and dyeing. Its applications can be found everywhere, ranging from the smartphone screens and packaging materials we encounter daily to high-end aerospace components and medical implants. With continuous technological iteration, this invisible "magical processing" technology will also play a role in more emerging fields — such as fabricating high-efficiency solar cell surfaces, developing new antibacterial materials, and optimizing the electrode performance of energy storage devices.

As a clean and efficient material surface modification technology, low-temperature plasma technology not only compensates for the performance defects of traditional materials, but also expands the application boundaries of materials. Leveraging the unique advantages of the "fourth state of matter", it endows ordinary materials with "special functions" and provides a new path for the green and high-precision development of industrial production. In the future, with the deepening of research, this technology will bring more surprises and continue to reshape our lives and industrial landscape.